Women Rise Founder Maliha Abidi on Art, Education, and Web3

There’s a delay between the moment that Maliha Abidi’s avatar flickers onto the screen and connects to her audio. In those first silent seconds, a chartreuse, stretched canvas reveals itself propped on the wall behind her. A crescent of a woman’s painted form, a graphic rose tucked into dark waves of hair, creeps out from behind Abidi’s silhouette.

The woman’s outline is of Madam Noor Jehan, an award-winning singer and actress who made waves as the first female Pakistani film director, inspiring countless generations of women. Abidi partially eclipses Jehan in the frame, which seems fitting because although she is in the early stage of her career as an artist-activist, they share a dogged prolificacy.

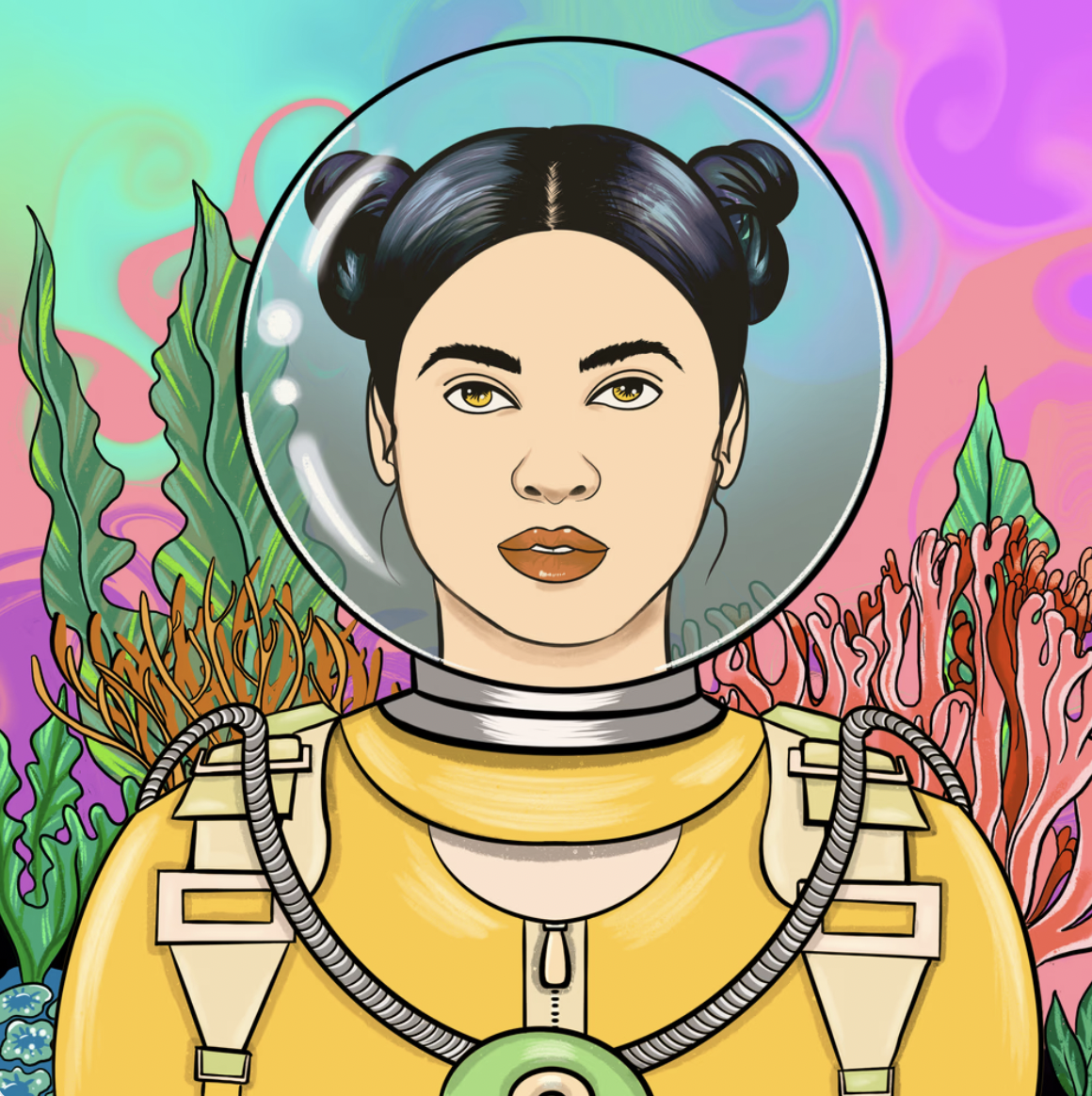

In the last fifteen months, the Pakistani-American polymath and founder of Women Rise NFTs has taken the Web3 community by storm. Her collection of 10,000 portraits depict imagined women imbued with a sense of power and purpose. Although fictionalized, they’re meant to stir the imaginations of a younger generation of women. Like much of her oeuvre, the Women Rise portraits share a similar aesthetic ilk: a lively color palette, minimal shading, and graphic lines. But Women Rise is about much more than art; the collection aims to raise funds and awareness for charities such as Malala Fund and The Girl Effect.

Since its launch in November 2021, Women Rise has ambitiously expanded from an extension of Abidi’s artistic practice to a more socially engaged platform that partners with other organizations — such as Qissa and CAMFED — which encourage women’s agency, equality, and education. What seems self-evident is, like the audience, she is hoping to inspire, Abidi reminds herself through the work what can be dreamt can also be made manifest.

We sat down with Abidi to discuss art as a vehicle for education, the importance of representation, and the need for more women in STEM.

nft now: Social justice is a huge part of your practice as an artist, author, and founder of Women Rise. What issues do you find most important?

Maliha Abidi: When it comes to causes that are close to my heart, girls’ education is, I think, at the top. Well, I tend to talk about women’s rights and girls’ education. Then connected to girls’ education, there are several other topics like mental health.

nft now: Do you find it challenging to focus on so many issues with their particular challenges?

MA: Yeah, they’re individually very big topics, but for me, they are still connected. For example, if you’re talking about women’s rights, you have to touch on girls’ education because there are 130 million girls are currently out of school. If you’re talking about girls’ education, you have to talk about the impact of period poverty. If we’re talking about that, then you need to also factor in how childbearing age plays a part in all of this. I’m not an expert on these topics, but I’m getting educated as I go. I want to use my art as a vehicle for learning and spreading what I’ve learned.

nft now: When I look at Women Rise, I see portraits of women standing in their strength and embodying a wide range of identities. What does the idea of representation mean to you?

MA: What I heard was that you should become a doctor, an engineer, or a lawyer. But in Pakistan, these careers are not high-paying jobs like they are in the U.S. If a girl is being encouraged to be a doctor, it’s so she can get a good marriage proposal. In Pakistan, it’s a phenomenon called the “doctor-bride phenomenon.” Your in-laws want a relationship to take place because you’re a doctor, and that makes you more desirable, but when you get married, you’re not allowed to practice your profession because your role has changed to mother.

That’s why I created my books — because I was seeing so many of these incredible women who are also in sports and art and educators and activists. And yes, there are doctors, but on their terms. Representation can open up that conversation within your family as well. I can say, ‘look at this amazing Pakistani woman who is a woman in sports.’ So it’s an internal dialogue as much as it’s an external one.

nft now: As you said, if you’re brought up with a dominant cultural narrative, a young woman may not even know what’s possible. As soon as you hear a story, whether it’s through art, cinema, or pop culture, that material has the potential to open up doors in a person’s imagination. What has opened up in your imagination since the inception of Women Rise?

MA: When Women Rise first launched, I remember there weren’t a lot of women-led [NFT] projects or projects representing women. I remember only a few women founders were paving the way. But I think at the time, it was also about just taking up space. There aren’t a lot of communities with people coming from my background taking up space in the crypto finance business. I wanted to create a project like Women Rise with a Pakistani team but then have a community that’s truly global [allowing us to] represent women’s rights on many different stages and different platforms.

nft now: One of your goals for Women Rise has been to encourage young women to go into STEM fields. Could you tell me about your journey into neuroscience and the challenges that you’ve faced?

MA: I’m currently not doing neuroscience anymore because each space is really demanding. Balancing art and my studies were always difficult. I was a broke student, but then I wanted to create this book, and I wanted to find time to create art too.

Somehow, I was working on the weekends at an art store to qualify for the employee discount so that I could buy the art supplies and for the book, my artwork, and train tickets so that I could then go to university five days a week. Around the same time, I opened up this side business selling chocolate-covered strawberries […] around campus. It’s always been very difficult balancing everything.

When it comes to STEM, we need more women in those fields. How is it that less than three percent of women are getting VC funding? How is it that that number is even less for women of color?

We need to encourage women and girls from a very young age and create environments that are nurturing. When it comes to STEM, it’s one of the most difficult places to survive, and the women who have paved the way need, like, we need to constantly celebrate them. Through that celebration, we are, in a way, planting seeds so that more women can come into this space. But it’s not just the responsibility of women and girls to do that, it’s the responsibility of everybody.