How ClownVamp Is Bringing Queer Visibility to Web3

Artists who use AI tools like Stable Diffusion and Midjourney often catch flack for producing work that is somehow cold, unfeeling, or lacking a distinctly “human” touch. The great irony buried just beneath the surface of this critique is twofold; first in that it glosses over the necessarily collaborative nature of such tools.

But the second rebuttal to that kind of decontextualized condemnation contains an almost poetic paradox: after all, the machine learning processes that form the foundations of these programs are part of a field of study that is specifically geared toward replicating human intelligence. In other words, reproducing the very qualities that we know define humanity.

It’s fitting, then, that artists are using AI tools to not only create individual works of art imbued with a living warmth but to build entire self-contained universes as well. Few operating in the AI art space are as adept at this as ClownVamp, the anonymous New York-based collector, visual artist, and AI art advocate who — over the span of two remarkable NFT collections — has crafted such a rich world of narrative storytelling as to blur the lines between fantasy and reality.

Chester Charles: The Lost Grand Master

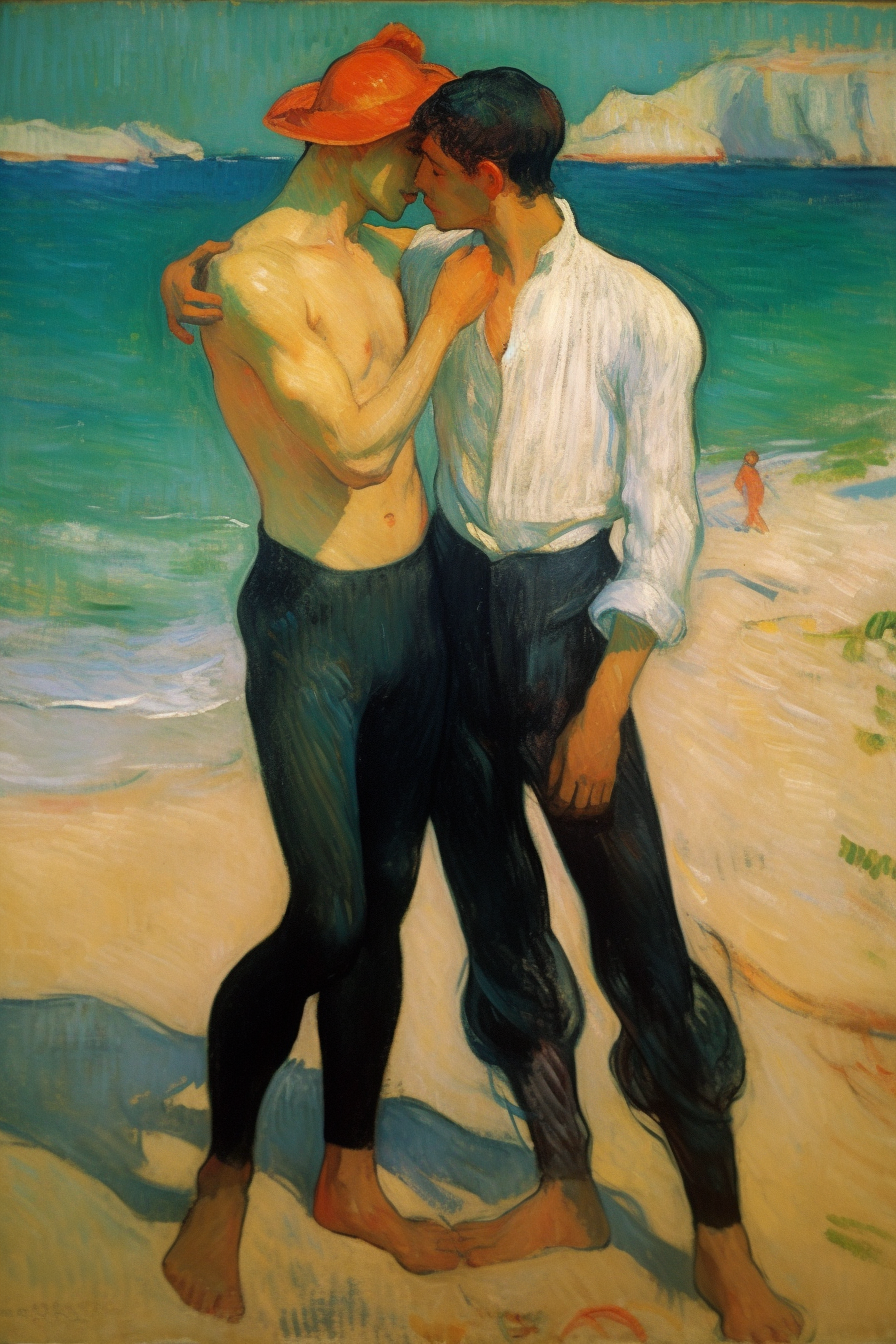

ClownVamp unveils his latest collection via a physical exhibition today, June 21, just a few days prior to New York’s annual Pride March in collaboration with SuperRare and Transient Labs. That timing is deliberate; the show, entitled Chester Charles: The Lost Grand Master, directly confronts the erasure of queer voices throughout history by using a fictitious vessel through which to explore non-fictional gay realities. With The Lost Grand Master, the artist has crafted a historical narrative around a figure named Chester Charles, an Impressionist painter who lived from 1855 to 1949 and whose works were never displayed during his lifetime.

The 23 works created by Charles depict the queer gaze during a time when outwardly gay individuals were ostracized from society in no uncertain terms. When happened upon by a Cleveland antique store owner during an estate sale, their discovery makes headlines, with many considering the works on par with the greatest Impressionist works of all time.

Curated by Mika Bar-On Nesher and Linda Dounia Rebeiz, the collection lives in a history of ClownVamp’s making that feels uncannily visceral and lived-in; the pieces in the collection even vary slightly in style, a nod to the evolving tastes and practices any real artist would exhibit over a lifetime. Each piece also comes with a 50-300 word inscription offering a window into Charles’ thoughts and desires.

The exhibition, which will take place at Canvas 3.0 at World Trade Center Oculus in New York, “represents a new form of storytelling combining written narratives, AI-generated imagery, and curation to examine the question of what could have been,” according to the show’s press release. That tagline is perfectly fitting for an artist who builds worlds that not only encourage the viewer to drag their fingers along the thin wall that separates fact from fiction but to find where it dissolves entirely.

nft now spoke with ClownVamp ahead of the show’s opening to talk about the importance of queer art in Web3, how a lonely childhood taught him the beauty of world-building and the joy of letting creative technologies lead you in unexpected directions

nft now: You’re a well-known collector, artist, and advocate of the AI art movement, but your journey in the crypto-art sphere began in the early days of Bitcoin. What sticks out to you about that journey today?

ClownVamp: In my early adventures in crypto, I would buy and then quickly sell Bitcoin, thinking I was really smart. That continued for quite a while where, every couple of years, I would get fascinated by crypto, and then I would buy it, and then I would sell it. And I’d sort of written it off.

Then NBA Top Shot started becoming a thing, and I just knew I should collect LeBrons. I didn’t really understand basketball, but I was quickly hooked on the idea of this digital object. So, I reapproached crypto with a much more open mind and was lucky to be early in PFP summer. I went fully down the rabbit hole; minting, flipping, trading. By the end of it, I had gotten burnt out.

But I realized I really did love NFTs, and I loved the idea of digital provenance. So I decided I was going to create a new, anonymous [social media] account and really just focus on collecting art. That’s where the genesis for ClownVamp was.

nft now: What led to your involvement in the AI art movement?

CV: I started collecting art, primarily on Tezos, and I saw some people minting stuff from the early Midjourney beta. I had seen GAN work before, but I’d never seen the sort of diffusion-based work that looked incredibly visually coherent at the time. Well, relatively coherent compared to [what Midjourney can do] now, even though it’s only a year and a few months ago when this happened.

“I think people [draw] very harsh lines between the things we think of as real and factual and historical and the things we think of as storytelling and fiction when, in reality, that line is very fuzzy.”

ClownVamp

I instantly got addicted to the storytelling potential of it as someone who’s been a big fan of alt-histories and alt-narratives. Everything in life is a narrative, and we engage in narrative building all the time. I think people [draw] very harsh lines between the things we think of as real and factual and historical and the things we think of as storytelling and fiction when, in reality, that line is very fuzzy.

I created my first collection, The Truth, which is a story of an Impressionist painter who lives through an alien invasion and paints scenes of it. Fast forward, and now my collecting is 98 percent AI-focused, and creating AI art has become the principal creative outlet for me.

nft now: Narrative storytelling features prominently in both The Truth and Detective Jack, collections that follow characters through a series of compelling events. What about narration appeals so much to you?

CV: I grew up as an only child, and I spent a lot of time alone. I think I was always engaged in my own world-building to keep myself amused. There’s often a lot of disparagement of only children, which I think is probably fair. But it’s also a really lonely thing, right? So, it was a lot of alone time. When I was really young, that came in the form of a sort of storytelling. I’m really interested in our conceptions of reality. In general, the stuff I like to engage with is also very focused on questions like, ‘What is real?’ and ‘What is truth?’

nft now: Your works in The Truth have a distinctly obscure, nightmarish feel to them, whereas the pieces in Detective Jack evoke mystery novel covers from the 1970s and 80s. Do you let your artistic vision be influenced by what AI models are capable of at a particular moment in time, or do you try to bend the technology and its abilities to fit your vision?

“As these tools become more perfect, I definitely find myself more attracted to the broken parts of them and the things that aren’t so perfect.”

ClownVamp

CV: I very much think about them interacting with each other. A big part of The Truth is its Impressionist Art feel, which I love, but it was also one of the things that Midjourney V1 could do coherently because it had this very melted-wax aesthetic, which played well.

That form of constraint is really fun and interesting for me. Later, as I was working on Detective Jack, I used mostly Midjourney V4, which had developed this amazing ability to blend things together. So, I was really heavily using the blend features, which allow you to create a lot more visual consistency. There’s always a back-and-forth between what it’s capable of and what I am expressing.

As these tools become more perfect, I definitely find myself more attracted to the broken parts of them and the things that aren’t so perfect. Sometimes I have a visual image I’m working toward, and then as I iterate, the models will feedback something unexpected. Sometimes that thing is terrible, sometimes it’s really helpful; it’s actually a better twist in the story.

nft now: I want to dive into Chester Charles: The Lost Grand Master, your latest collection. As a gay artist, the themes involved obviously touch on some deeply personal issues for you. What led you to want to directly address the idea of censorship of gay artists in history at this point in your artistic journey?

CV: I’ve been working on Chester Charles for 10 months. I was using an earlier version of Stable Diffusion and creating some concepts around the idea of fatherhood in a kind of historical art style. Early Stable Diffusion had this AI artifact around twinning. When you try and create something that’s a landscape or portrait, it views it as two squares, and sometimes it’ll twin the image.

As a result, the model really wanted to show me gay dads. Every single image was two dads holding hands with their child. That created this immediate feeling where I realized that I hadn’t seen gay images like this. And that’s kind of bizarre; the fact that this is just missing from my visual history and visual language is really strange. As a gay man, I felt that this was actually very soothing to see.

I started doing more exploring and creating all of this “old” art that was very gay. I was doing it basically for personal satisfaction. I’ve always been open about being gay, but I hadn’t really created that much gay art. In The Truth, my character, who’s a painter, is gay, and he finally came out as gay in this sort of story arc. That those pieces were the best-selling pieces to date of the entire series was a really emotional and dramatic moment for me.

I started iterating on some ideas of seeing this thing that was missing from our history and having this very visceral reaction. Almost like, ‘Oh, my God, there’s all these people who couldn’t express themselves in the way they would have in modern times.’ And they’re just lost to human history. It just sparked all these complicated feelings. I thought that’s a really important feeling that I could express and something I want to express.

“We don’t have a ton of really well-known gay crypto artists and queer crypto artists.”

ClownVamp

I started thinking about ideas; I talked to Chris from Transient Labs, I talked to Mika from SuperRare, and I eventually came to the idea that the ideal way to tell this story is through the lens of an artist retrospective. An artist retrospective shows a person’s history, both intrinsic to them but also contextualized within a time and place. It shows their development as a human, it shows their development as an artist, and it shows how those two things intersect. For telling this story, that was the perfect thing.

So, in this fake career retrospective for an artist that didn’t exist, there’s a very straightforward wink. But if you’re skimming too quickly, you might not catch the wink.

nft now: You’ve mentioned in the past that you feel a marked absence of gay art in the crypto art space. Why do you think that is?

CV: We don’t have a ton of really well-known gay crypto artists and queer crypto artists. As a result, I think there isn’t this internal permission structure [that lets people say], ‘This is something I can engage with.’

It’s something I want to try to make some positive impact on because my general message to queer artists is that the water is pretty warm. I think people in crypto, they definitely have a libertarian leaning. In general, people are open. I think a lot of it has to do with role models. Obviously, the first wave of crypto art was and is pretty specific.

My hope is that, as the years go by and as this movement matures, you will see more diverse voices. But I don’t think there are structural obstacles to gay artists [in crypto] that are worse than traditional art.

nft now: You’ve also said that the idea of human potential plays into a lot of the work you make and the advocacy you do in the space. What about this idea appeals to you so much?

CV: I try to spend a lot of energy talking to people who are into AI art, encouraging them to view it as this big human potential unlock. In terms of my art, I’d say that a lot of it is meant to make you view things differently. I’m trying to show, not tell.

One of the biggest compliments for me is seeing other people riff off of ideas I’ve used in my collections with storytelling formats. I’m not precious about any idea. I want people to see an idea and do something similar. I want them to get excited. All of that stuff is really fun. It also gives me the mental permission to keep pushing and trying new and different things. I always want to be experimenting and exploring.

I like to think a lot of my art has a hopeful bent to it. I’m also very pragmatic. It’s important to give people resources and tools and access to all these things. But a big part of what I want to do in my life is to try and build other people up.