How NFT Misinformation is Harming the Environment

In 2019, wildlife photographer Frank Liu took a shot of a spotted Zebra. The photo was covered in National Geographic, Forbes, Smithsonian Magazine, and featured on the cover of several South African publications. Today, Liu is trying to move beyond his Web2 legacy and traditional media. He’s traveling the world building a community of artists interested in facilitating wildlife conservation using Web3 technologies.

But there’s a problem.

A combination of blockchain fear-mongering and misunderstandings about NFTs and the environment have thwarted his conservation efforts — and what might be one of the greatest funding opportunities many small NGOs have ever seen.

The journey into Web3

“I started taking photos in university,” Liu tells nft now. “In 2016, after my first trip to the Maasai Mara Reserve in Kenya, my photos were published in The Sun, The Guardian, and The Daily Mail.”

Three years later, Liu took the now-famous shots of a spotted baby Zebra. If you Google “spotted Zebra,” the first five articles are all about Liu’s photo. Even ChatGPT knows the answer to the question, “Who took the photo of the spotted zebra in 2019?” Liu was in the running for the Natural History Museum’s Wildlife Photographer of the Year award once or twice. But he only reached the top 300 — the competition attracts nearly 50,000 entries.

And then the pandemic happened.

Liu says it ended his livelihood. Two years of preparatory work with agencies, tour operators, guides, and safari lodges went up in smoke.

Then one of Liu’s former colleagues explained Web3 to him. The colleague had been working with a blockchain company called Empowa that was using DeFi to help remote communities get housing in Africa. At the time, Liu wasn’t a complete stranger to blockchain. He had bought his first bit of crypto in 2017, but he hadn’t paid it much mind since then. The pandemic changed matters.

Liu and his colleagues decided to put together a wildlife NFT project on the Cardano blockchain, both to support themselves and to raise funds for NGOs focused on wildlife conservation.

Liu says the team selected Cardano because it was more sustainable than some other chains. It also had its own fund, and users would vote on projects they wanted to see developed. Liu’s analysis indicated that the Cardano community tended to vote for projects with a real mission and impact, so it seemed like a natural fit.

But misinformation made executing the project an uphill battle.

Troubled waters

Because of the royalty features embedded in smart contracts, NFTs can provide creators and the organizations they support with a recurring, reliable source of revenue. In this regard, Liu notes that NFTs “represent a more sustainable income source for these [smaller] NGOs than other sources.”

Liu’s idea was to create an NFT project akin to trading cards. Personally vetted artists would submit their photographs, and these would be turned into collectibles with icons on them. These icons would show the artist’s name, the animal’s scientific name, information on the animal’s habitat, whether the population is increasing or decreasing, and other key details that help raise awareness for that species.

The first challenge Liu experienced came from artists. Many of the creators he contacted said they were concerned about sustainability issues stemming from blockchain technologies. Despite his attempts to assuage their fears and explain how blockchains actually work, not everyone Liu approached agreed to help him. Several photographers remained unconvinced, positive that NFTs were damaging the environment, condemning the entire practice as unsustainable.

Likewise, the NGOs Liu approached cited concerns over sustainability. After speaking with them at length, Liu says it became clear that they didn’t understand the difference between chains or consensus models.

This poses a real problem.

Liu typically approached niche NGOs focused on a particular species or geographic zone. Because they are so niche, their work is vital. No one is there to take over if they don’t survive. According to Liu, these niche NGOs are also continually in survival mode — spread far too thin and desperate for funding. That’s precisely why NFTs could work so well for them.

An NFT project could bring them urgently needed funds in excess of social media campaigns and other slow-burn methods. In exchange, these NGOs could provide unique content for NFT holders because of their niche position. Liu explains that this value could be original footage, walkalongs around habitats, and other content that would otherwise cost tourists far more than the price of a single NFT. It’s a win-win.

But according to Liu, things are getting increasingly difficult and looking more and more bleak. People see sensationalist articles that lack any context and take them as truth.

And sadly, Liu isn’t the only one having problems. Many who have attempted to launch conservation efforts via NFTs have been met with contempt and watched as their projects floundered and failed due to bad information.

A tale of two wildlife foundations

Nowhere is the mass misunderstanding of Web3 more apparent than in the NFT projects launched by the World Wildlife Foundations (WWF) in Germany and the UK. The first — Non-Fungible Animals — was a resounding success, raising nearly $300,000 for highly endangered species. The latter — Tokens for Nature — which ran on the same chain, was a bloodbath.

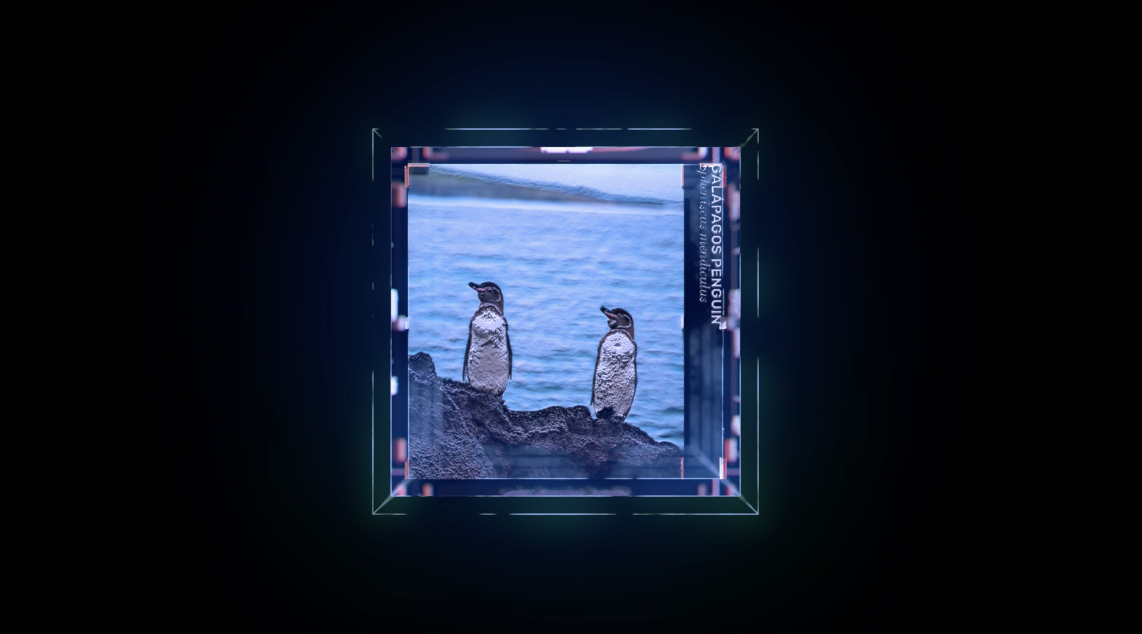

Non-Fungible Animals — named to represent how one animal and species can never be replaced by any other — is still going strong nearly one-and-a-half years after it’s launch. Each animal represented in the project — the Amur tiger, Baltic porpoise, Persian leopard, and others — had exactly the same number of NFTs created for it as there are members of its population. For example, the Giant Panda collection contained 1,864 NFTs because there are only 1,864 Giant Pandas in the world. The Giant Ibis had 290 NFTs. The rarer animals were more expensive.

The project was ultimately widely supported by advertising agencies and publicists.

Anna Graf, the Web3 innovation Lead at Arvato systems, was an independent NFT consultant in 2021 when she was asked to advise on the German WWF NFT project. “I found [the project] very interesting,” she tells nft now, “because it was the first on-chain NGO project that I had ever heard of.” Graf connected the project with well-known NFT Artist BossLogic, who had previously worked with the likes of Disney and Marvel Studios.

On the sustainability side, the German WWF project chose Polygon. They also created their own marketplace so that it was possible to seamlessly pay with a credit card through MoonPay, which was “quite a hurdle” at the time, Graf says. Today, MoonPay integrates with OpenSea and other marketplaces. A year and a half ago, that wasn’t the case.

Another element that made the German project successful was a powerful storytelling technique, Graf says. The group leveraged advertising agencies to weave in the narrative of the number of these animals into the story. The project promoted the concept of art on chain as opposed to only buying NFTs for investment purposes. In this sense, the project became a visionary one and distanced itself from the cash grabs and “too good to be true” 10x and 20x ROI promises that plagued early and mid-2021.

“For us, it was never about the funds,” a WWF Germany spokesperson told The Verge after the WWF UK debacle. “It was about raising awareness regarding the species’ extinction.”

In contrast to the success of Non-Fungible Animals, two days after launching its NFT project, WWF UK was backpedaling and offering nearly $50,000 worth of refunds to NFT purchasers. So why did it fail where it’s counterpart flourished? Misinformation.

“[WWF UK] totally failed,” says Graf, “because instead of focusing on the art, they told people that Polygon is a chain that is totally carbon neutral or needs less carbon than drinking a glass of water.” It’s impossible to accurately determine the cost of a single NFT transaction because they are processed in blocks. WWF’s statement wasn’t, therefore, entirely truthful. “So they were kind of lying, and this brought up a big discussion,” says Graf.

The WWF UK soap-boxing regarding the carbon emissions of NFTs takes on a bitter taste when you consider that WWF received a $400,000 grant from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund in 2019 — a family that grew fat on a century of oil production.

Graf believes its possible that the WWF UK division wasn’t as accurately advised on the technical elements of the project, leading them to furnish erroneous information about it. But she says she was not involved in that project and cannot claim this with complete certainty.

The drumbeating helps no one

Small NGOs are dying. They are overwhelmed. They need funding now. Their loss would be a catastrophe for the environmental zone they cover. NFTs open a realistic door to that funding. While greenwashing the blockchain isn’t the solution, it’s important to promote accurate information and context about its energy usage in comparison to other environmental culprits.

To begin with, Netflix uses up to 36,000 times more energy than PoS Ethereum. PayPal uses 100 times more energy. Wherefore the outcries for NGOs accepting donations via PayPal? Global Data Centers are right up there with energy production — a massive 78,000 times more than PoS Ethereum.

You’d think that gold mining would be the worst culprit. But nope. And neither is Bitcoin. The greatest planet killer on the scale of energy consumption, coming in at 94,000 times more consumption than PoS Ethereum is YouTube. But where are the crowds demanding a takedown of the latest WWF YouTube video to raise funds?

And don’t forget to shut every bank down on earth. JPMorgan emitted 766 metric tons of CO2e in 2022, and Bank of America didn’t fare much better. By the logic of the Anti-NFTers, NGOs shouldn’t accept funds through banks, either.

The list goes on. At some point, the arguments become senseless and groundless without context. And they are actually causing more damage because NFTs may represent the first breath of hope for small NGOs to get their heads above water in years.

Getting an NFT project off the ground is hard enough without all the anti-blockchain rhetoric. But such rhetoric — mainly, the misinformation that comes with it — cements any thoughtful hesitation into complete non-cooperation. “They just read the headlines,” Liu says of people who haven’t had much exposure to blockchain. “They say it has a lot of environmental impact, and so it goes against what they’re trying to do.”

Liu believes the technological barrier to entry for NGOs is much lower now than a year ago. But the recent spate of negative crypto news has worsened the sentiment.

“It’s still too early to get them on board,” Liu says. So he is focusing now on creating a worldwide collective of personally vetted artists called “Dreamxrs,” all with the similar wildlife conservation goals, that he can bring together for an NFT project in the future “when the time is right.”

Hopefully, when his team is ready, the world will be more informed on the subject and allow NGOs to be helped by one of the best solutions to come their way in years.